Excited to introduce Nicole Lynn Evans to the Proof Positive community – especially as we close out another month celebrating Disability Pride! Take it away, Nicole…

I learned the importance of self-advocacy by watching my parents advocate for me after my 8th grade graduation was inaccessible to me.

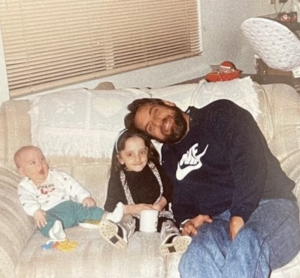

A little background on me – my name is Nicole Evans, I’m a woman with a disability, I have Osteogenesis Imperfecta, a genetic bone condition characterized by fragile bones that break easily. I have been using a wheelchair since elementary school.

Now, let’s get back to my 8th grade graduation ceremony. Picture this — A warm spring day in Southern California. It’s the late 1990s. The Americans with Disabilities Act is not even 10-years-old. There is an outdoor cement stage four feet off the ground that is only accessible via staircase (I think you can see where this is going). The graduating students sit in folding chairs on the ground level facing the stage. And behind the student body are the families that came to watch — including my mom, dad and grandparents!

The students without mobility devices walk up the stairs, collect their diploma, walk across the stage, and back down another set of stairs, then return to their seat. But me? There’s no ramp, and I obviously can’t get up the stairs in my wheelchair. When my name is called, I roll my wheelchair to the side of the stage on the ground level, reach up for my diploma, and return back to my seating area.

To put it mildly, my parents are…not happy. Frankly, they’re pissed. But let me be clear, they’re not mad at me! They’re mad at the system.

I don’t think this was in our societal lexicon at the time, however, please forgive me if it was — what we were dealing with was structural ableism — the physical inaccessibility that effectively denies entry and access for people with disabilities. These include barriers to physical structures such as buildings and public spaces, but also include barriers to infrastructures like mass transit systems, and other organizational systems that are needed for the operation of society.

Furthermore, autistic people report structural ableism in the forms of the high value placed on verbal communication by our society or a requirement such as a job interview, or the expectation that showing interest in another individual requires making eye contact.

Let’s back up for a sec — Our graduating class rehearsed the graduation proceedings the day prior. I knew that this was the way it was going to go down for me. But in all honesty, I didn’t yet understand that what was happening was not ok. To my young 13-year-old self, this was just how things were, and I hadn’t realized that my access needs were not being met. Again, this was the late 90s when the Americans with Disabilities Act hadn’t fully settled into the public consciousness, let alone in my orbit.

The strong reaction my parents had to me not having an accessible graduation experience to receive a diploma that I earned — just like everyone else — and most importantly, the action steps that my parents took to ensure future access for me at school — was truly a defining moment in my life.

Watching my parents engage with the schools to solve this access issue taught me how to self-advocate. I learned that I have access requirements and that I have a right to that access. I deserve to take up space.

I learned that a critical part of ensuring my participation and opening opportunities for myself was being able to articulate my access requirements. I learned to say what I need. The truth of the matter is that you can’t rely on institutions to guess and get it right. You must meet them halfway and help solve the equation.

Now, I need to mention that, at times, I know that this can feel scary. I get it. I’ve had moments in my life where I was scared to speak up about my access requirements for fear of sounding difficult or squandering an opportunity. In moments like these, I am aware that when I speak about my access requirements, it will help the next person with access requirements get what they need faster and easier.

Shifting to this perspective (a top character strength for me!) has helped me to reduce my anxiety and speak more confidently about access, because it takes the pressure off it being about me and focuses it to being about having greater access for all.

It is critical for organizations and institutions to also have a shift in perspective and recognize that it’s impossible for them to know and pre-determine every access need and requirement. It’s crucial for them to have an open-door policy where these access needs can be heard and solved, with the same goal of increasing access for us all. They must meet us halfway as well.